Border Wall Expansion Threatens to Wipe Out America’s Last Jaguars

Matthew Russell

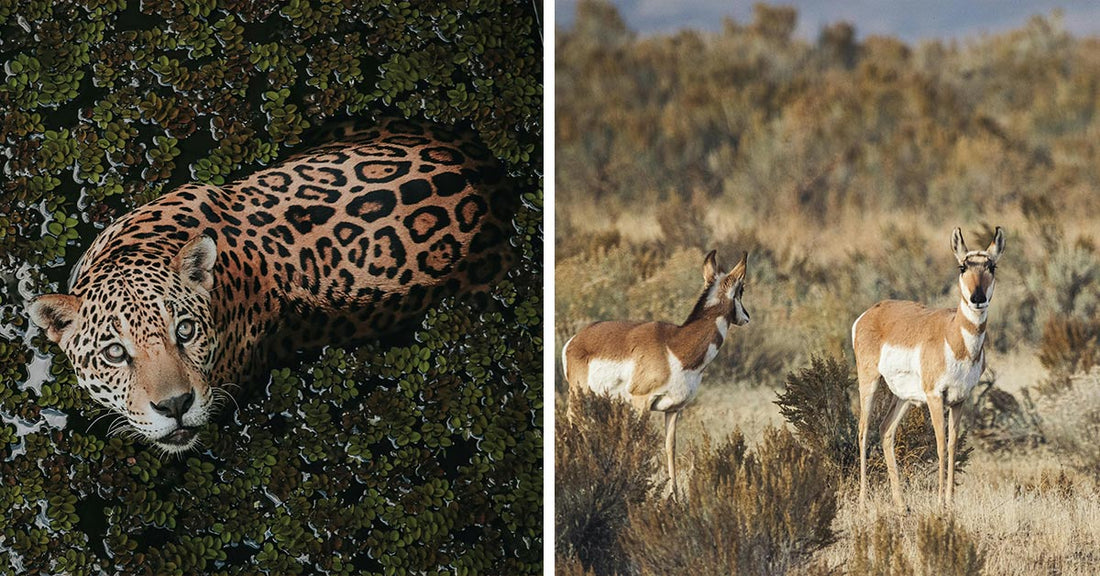

A lone jaguar, known to researchers as Jaguar Number Four, was photographed moving through Arizona’s San Rafael Valley — a rare and hopeful sign that the region’s wildlife corridors still function. His return follows an extended stay in Mexico, retracing a route that has connected species across the U.S.-Mexico border for millennia.

Conservationists warn that a planned 27-mile wall through this corridor could sever one of the last remaining pathways for jaguars, ocelots, mountain lions, and other wide-ranging species, making future crossings impossible, the Washington Post reports.

The San Rafael Valley is not just another patch of open land. It lies within the “Sky Islands,” isolated mountain ranges in the Sonoran Desert where temperate and tropical species converge. This landscape harbors an exceptional diversity of life, from desert tortoises to Mexican gray wolves, and forms the northernmost range for the jaguar. Blocking it would be permanent, AZCentral reports — the loss of a genetic bridge between populations and the collapse of potential recovery for some of the continent’s most endangered animals.

Jaguar Number Four is the only known resident jaguar in Arizona.

Barriers That Stop More Than People

Modern border wall designs are formidable: bollards up to 30 feet high, spaced only four inches apart. Animals larger than a bobcat cannot pass, and smaller openings — roughly 8.5 by 11 inches — are scarce. One study cited by Wildlands Network documented only 13 such openings in a 70-mile stretch, providing no passage for species like black bears, white-tailed deer, or mule deer.

For predators and herbivores that roam over hundreds of square miles, these barriers fragment habitat and restrict access to food, water, and mates. The result is genetic isolation, smaller population sizes, and a reduced capacity to adapt to environmental changes — a dynamic scientists describe as creating “zombie species,” populations doomed to eventual extinction, Stanford, reports.

Bighorn sheep, pronghorn, and mountain lions rely on seasonal migration routes.

Species Already in Decline

In the borderlands, wildlife movement is not optional. Mountain lions and pronghorn antelope rely on seasonal migrations. Bighorn sheep cross valleys to follow shifting forage as temperatures rise. Jaguars and ocelots depend on dispersal routes to maintain contact with breeding populations in Mexico. Even partial walls can drive local populations to collapse by cutting off these life-sustaining movements.

Data collected along Arizona’s border show the stakes. A multi-year camera study across 100 miles of barriers found an 86 percent drop in successful wildlife crossings where steel walls replaced vehicle barriers, Wildlands Network reports. For large mammals, success rates fell to zero in some segments. Small wildlife openings improved passage for certain mid-sized species but left larger animals blocked entirely.

Jaguars in Arizona depend on connections to breeding populations in Mexico.

Beyond One Jaguar

The focus on Jaguar Number Four reflects the urgency for a species clinging to the edges of its historic range, but the threat extends across an entire web of life. The U.S.-Mexico border traverses more than 1,500 native species’ habitats, cutting through forests, grasslands, rivers, and deserts. Many of these ecosystems are already stressed by drought, development, and climate change. When the wall blocks animals from moving toward cooler or wetter refuges, survival odds plummet.

Researchers stress that these losses carry economic and cultural costs. Wildlife watching, hunting, and fishing contribute billions annually to border state economies. For Indigenous nations, such as the Tohono O’odham, species like the jaguar have deep cultural and spiritual significance.

The Sky Islands region holds one of the highest biodiversity levels in North America.

Alternatives and a Narrow Window for Action

Advocates argue that border security and wildlife conservation need not be mutually exclusive. Technological monitoring, targeted enforcement in high-traffic areas, and larger, strategically placed wildlife passages could allow species to move while meeting security objectives.

But those measures require political will — and time. If construction moves ahead in the San Rafael Valley, experts say the last genetic link for jaguars in the United States will vanish. For wide-ranging species already hemmed in by roads, development, and climate shifts, it could be the final barrier they cannot overcome.

Click below to make a difference.